Let’s time travel back to 17th century Italy. Some things we don’t have to imagine as the parallels still exist today- such as the golden age of art and music and philosophy being ravaged by war, plague and famine. (oh, and the Catholic Church doing most anything in their power to remain relevant and in control by continually spewing propaganda…)

History often repeats itself. Anyway…

During this time and many many years before, the artistic output was governed by religious dominance— a spunky move by the Catholic Church to re-establish its importance and grandeur within society after the Protestant reformation… as planned and implemented in Council of Trent. Artists at the time followed the culture, diverting back to the Renaissance principles of beauty and a renewed embrace of classicism.

From the middle to end of the 16th century, a more dramatic style of creation began to take shape. Though Baroque piggybacked off of the classical renaissance style, the polarities between the two styles can be easily identified across all mediums: from architecture, to painting, and even sculpture.

Baroque compositions are much more emotionally charged, larger-than-life, and utilize an intense dramatization of light known as chiaroscuro. The imagery is insanely life-like, ornate, and rich in color and contrast.

In this segment of art history, we find the dramatic works of Caravaggio, Rubens, Vermeer, and Rembrandt.

It’s where we also find one of the most influential and forgotten painters of the 17th century, Artemisia Gentileschi.

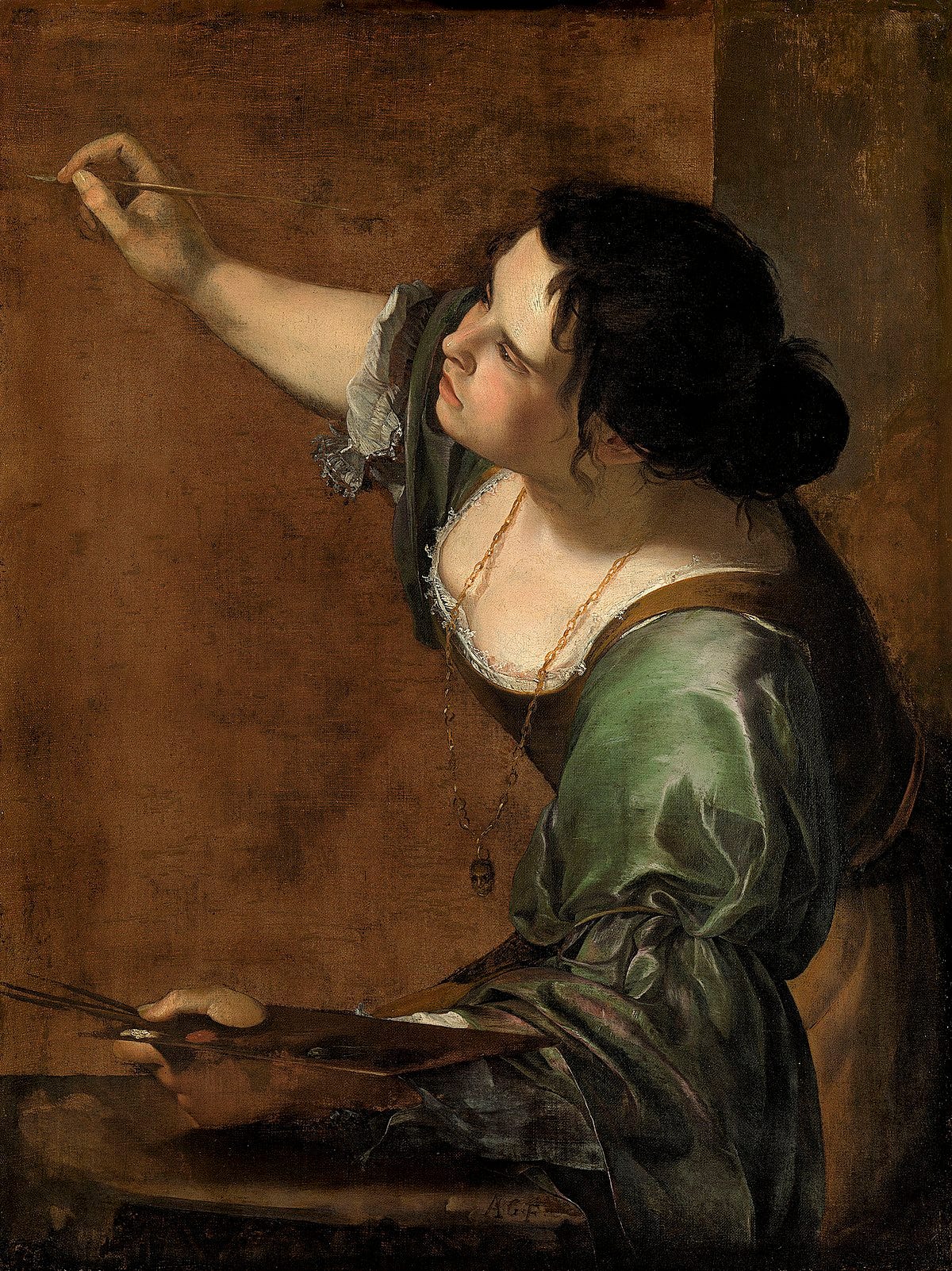

Gentileschi’s self portrait

I have sat through four years of art history in undergrad, earning an art history minor. that’s two art history classes per week, for six hours a week. I sat there in those 6-9pm classes, trying my hardest to stay awake, (and if i’m honest) bored to tears most of the time, obsessively writing hundreds of notecards in the library the other half— trying to memorize centuries and centuries of information, praying to the art gods that I would have the memory bank to pass my praxis exam.

In all of those hours and studies, the name Artemisia Gentileschi was never murmured. Not in a lecture, not in a book, not in a paper. I’m hopeful that this may be different, 12 years later.

Why are we erasing women from art history? Backtrack— history, in general. I wonder how many stories of how the world came to be without the true recognition of our most vital humans.

I also question my own lack of awareness in these academic spaces; where I did not question why I only learned of Mary Cassatt and Georgia O’Keeffe. How did I never pause and ask, there must be more than this? Many of the art history professors I had in undergrad were also women. Why were we not showcasing the hidden undertones of erasure and problems this causes for the Truth?

Back to Gentileschi.

Her genius is overlooked, why? *sexism has existed since the dawn of time*

During her lifetime— and many lifetimes before and after— religious dominance had the power to direct and inform the content and climate of society's artistic output. While Gentileschi’s work is no stranger to this, she was still able to revolutionize conventional portrayals of female protagonists within these usual biblical and mythological tales. She employed her role as an artist to critique the male-dominated structure of society and to redirect attention toward female empowerment and autonomy. The female figures in these biblical tales were presented as heroines with agency, moving away from being seen solely through the lens of male perception. This fresh approach empowered these characters with a renewed sense of strength and control, an aspect overlooked by earlier artists— and her male counterparts.

Yes of course we can notice the sexism and it’s correlation to a modern day patriarchal society, but there is another narrative woven through out the life of Gentileschi and her work, one that is also very prevalent in our modern society and the way we view women. It is more nuanced. Let’s talk about it.

But first, a little more background:

A life of artistic talent,

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in 1593 in Rome. The daughter of an Italian Baroque artist, she began her young life apprenticeship, studying under her father and landscape painter, Agostino Tassi— both followers of Caravaggio’s dramatic realism.

Let’s also note here that she was the first female to be accepted into Florence’s prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno and collected by the Medici family. She was fucking brilliant. Even the sexism found within the church and the art world could not deny the insane level of her gifts. Artemisia's re-evaluation as an artist has highlighted a fresh recognition of her technical mastery, particularly her adeptness in chiaroscuro. On the same level as Rubens, Van Dyck or Vermeer. Aka all those fuckers who take up 90% of The National Gallery in London or the MET in New York City. *Only 20 works out of 2,300 owned by The National Gallery are by women*

Artemesia created some of her most masterful works all before the age of 25: and some of her most notable works, such as 'Madonna and Child' and 'Susanna and the Elders', were created when Artemisia was only 20 and 17.

If we look at her rendition of Susanna and The Elders, we are able to notice firsthand the shift in the work from a female perspective— something that was completely unspoken for at the time.

Let’s go down a quick rabbit hole:

The story of Susanna and the Elders is found in the Apocrypha, specifically in the Book of Daniel, in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Old Testament.

This story revolves around Susanna, a virtuous and righteous woman married to Joakim, a prominent man in Babylon. Susanna was renowned for her beauty and devotion to God. Two elders of the community, who also held positions of authority, became captivated by Susanna's beauty and conspired to blackmail her.

One day, as Susanna was bathing in her garden, the elders, overcome by desire, attempted to coerce her into having sexual relations with them. They threatened to accuse her of adultery if she refused their advances. Faced with this terrible choice, Susanna maintained her integrity and refused their demands.

The elders, outraged by her rejection, accused her of adultery, leading to a trial. Susanna firmly defended her innocence. In a dramatic turn of events, the young prophet Daniel intervened. Through astute questioning and separate testimonies, he exposed inconsistencies in the elders' stories. Eventually, the truth emerged, and Susanna was acquitted while the elders faced the consequences of their deceitful actions.

The narrative presented a compelling opportunity for artists to explore a voyeuristic theme… and but of course— female nudity.

A women’s terror being utilized as an excuse to study and portray the female form without question from the church. Women’s safety and experiences have been commodified since the beginning of time.

Many artists within the 16th and 17th centuries chose to recreate this subject. These include Rembrandt, Tintoretto, Guido Reni, Paolo Veronese, Ludovico Carracci, Rubens, Van Dyck and our girl, Artemisia Gentileschi.

What’s even better *sarcasm* are the numerous renditions of the situation from male perspective… where Susanna is represented as aloof and even welcoming. Typically, Susanna is depicted as oblivious to the elders' presence, sometimes even appearing to welcome them in a flirtatious manner. I wish I could say I was surprised.

Many artists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries chose this subject. These include Rembrandt, Tintoretto, Guido Reni, Paolo Veronese, Ludovico Carracci, Rubens, Van Dyck and Artemisia Gentileschi.

In the painting by Tintoretto, as seen right above this— Susanna is represented as a vain, ignorant woman— much more preoccupied with her reflection in the mirror. This causes her to be unaware of the elders peering at her from behind the wall. Oh how we love to victim blame, even in the 16th century.

Luckily, in other versions, paintings begin to nod toward the violence threatened against Susannah, as shown in Ludovico Carracci’s version— years later in 1616. Our main subject is brightly lit, in stark contrasted against the elders who loom over her, attempting to pull off her cloak.

“A young woman crouches in the bottom right-hand corner, trying to cover her nakedness with her cloak, while two bearded men leer at her and pull at her clothes…”

Gentileschi went on to portray her own version of Susanna, in 1610, when she was just seventeen years old.

Here is Gentileschi’s depiction of the story:

Gentileschi focuses on not only the dramatic elements of the story, but also from the female perspective.

Artemisia positions Susanna near the forefront of the scene, seated upright on a bench… making her the focal point. Susanna visibly recoils from the dark, menacing figures of the men positioned above her, seemingly colluding in a threatening manner. This deliberate arrangement creates palpable tension within the composition. Susanna's eyes and mouth are partially open, conveying her alarm at the men's behavior. Artemisia utilizes her brilliant Chiaroscuro, skillfully playing with light and dark elements, a crucial aspect of her narrative interpretation. You can see that Susanna is bathed in radiant light, while the two men are shrouded in dark tones and shadow. In Artemisia's rendition, there is a clear delineation of the victim – Susanna. Without question.

To continue reading this week’s rendition of The Art Of: would you consider upgrading to paid? For 6 dollars a month, you will receive monthly writings directly to your inbox, and perhaps soon — a podcast ;)

Back to the nuance behind Artemisia’s Life:

I am going to insert a trigger warning here for rape, assault and torture. Please take care of yourself x

Women have been fighting back against injustice and male violence for as long as they have been able to record it, and her work of Susanna and the Elders depicts this beautifully. But Gentileschi’s life work is often defined and overshadowed by something that happened to her, just a few years after this work was created.

The year after Gentileschi created this work, she was raped by her painting tutor, Agostino Tassi.

Upon learning of Agnostino's assault on his daughter, Gentileschi’s father actually took immediate action by having him arrested. A lengthy and insanely traumatic seven-month trial followed, proving to be a distressing experience for Artemisia and resulting in irreparable harm to her reputation.

During the court proceedings, Artemisia confronted Agostino with his prior promise to marry her after the assault, a detail brought to light during her sworn testimony.

As written on Repaint History, “The judge in Artemisia’s case allowed the use of a sibille, a thumbscrew torture device. But it was not Agnostini who the judge interrogated with a sibille but Artemisia. AS she was tortured, Artemisia screamed at Agnostini, “This is the ring you gave me and these are your promises!” Agnostini accused Artemisia of being an “insatiable whore” and denied raping her. Had Artemisa not been a virgin at the time of her rape, under Roman law, what Agnostini did to her was not rape. It was only when a Gentileschi family friend testified that Agnostini had boasted about the rape that the judge convicted him. Agnostini served one year in prison. Transcripts of his trial survive today.”

During the trail, Artemisia completed her perhaps most well-known work, Judith Slaying Holofernes.

The story of Judith and Holofernes is recounted in the Book of Judith and Catholic editions of the Bible. Like the story of David and Goliath, it was a popular subject the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Gentileschi’s depiction of the scene is known to be the most graphic and vivid, with details to ensure the emotion of rage is felt across the composition. Her interpretation of the piece is different from her male counterparts’ renditions… emphasizing the intensity of the physical struggle, the amount of blood spilled, and the physical and psychological strength of both women depicted. In other renditions of the story, the servant woman seems to be shocked and wide-eyed by Judith’s actions, while Judith seems hesitant and recoiled by her task.

But in Artemisia’s version: the two strong, young women are found working in unison, their sleeves rolled up, gazes fixed, their grips firm. Her version of Judith does not show remorse or hesitation, and there is an intensified realism placed on the blood that violently spurts from the neck of Holofernes.

Historians argue that Artemisia identifies with the protagonist of the story in a way her male counterparts did not, and was able to showcase her own experience of rape and the trail through this work. She was able to recreate biblical paintings that depict her life injustices, doing the impossible for the time by personalizing her own story, weaving it within the classical compositions.

Judith Slaying Holofernes is an autobiographical feat created, for the first time, with a unique female perspective that was, surprise surprise, overlooked at the time.

While her work during this time in her life very clearly has ties to all that she was put through during this traumatic experience, there is nuance here regarding a women’s work being defined by her rage. Rage that is, in my opinion, very intellectual and deserved.

Unsurprisingly, the assault has become the predominant perspective through which her artistic achievements are perceived, and grossly oversimplified. The intense themes in her artworks have been seen as manifestations of intense and angry emotional release, and the focus of her voice being that of an angry woman who survived a rape trial.

While I suppose it’s reasonable to be captivated by her work within this context, especially considering the persistent prevalence of sexual violence against women and the tendency to disregard women's narratives of such experiences—- I think it’s just as important to see Gentileschi’s work through the lens of technical craftsmanship and brilliance, just as we tend to celebrate her male counterparts.

Why as society do we want so badly to strip women down to what has happened to them, or the rage they express because of it?

Many of the women in our modern and previous timelines have large, dark shadows cast over not only their accomplishments, but their character as well. We love to place them under a microscope and dissect their every reaction to the identity we’ve given them, enjoying commentary on what their reaction, life and healing process should look like.

Similar to Christine Blasey Ford being a successful professor and researcher of psychology, but specific details regarding her contributions to the field are not widely known. Her most publicized life experience is related to her testimony during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings in 2018 where she accused then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault— and the world was able to tear her apart for what she did and did not do as a young teen whose world had been turned upside-down. Instead, her life is stripped down to a “witness lacking in credibility.”

Similar to Britney Spears being mocked and remembered for her shaved head and public collapse, after years of harassment, degradation and abuse.

Similar to Monica Lewinsky’s life being stamped with an adulterous A, to forget that she was a young 21-year-old recent college grad with an unpaid internship through a connection with a family friend.

Similar to Lizzette Martinez, Lisa Van Allen, Jerhonda Pace and the many women whose lives have been watered down to the idea that they ‘should have come forward earlier’ after surviving years of abuse at the hands of singer R Kelly— whose records are still played in clubs all around the globe today.

and less alike than those mentioned above, it is also similar to Taylor Swift taking a sip of champagne after a sexist joke at an awards show, not hiding the annoyance for when her record-breaking success as a singer, writer and performer are once again, attempted to be outweighed by her appearance at a football game for a boyfriend.

Why can we never allow women’s work, character or life lived stand on their own, without connecting it to something other?

Several years ago, the news was plagued by a story of a Jane Doe who had been assaulted behind a dumpster outside of a fraternity house. The world dissected her and stripped her down to merely an unnamed victim— an unconscious, intoxicated woman. In her memoir, Know My Name, Miller not only reveals her true identify, but the ways in which she had to recover her sense of self due to the ways society had stripped it back— diluting her to only what happened to her on that fateful night. In her captivating book, Miller explains the nuance of having her identify taken from her, and the reclamation of her sense of self by releasing her name and sharing her story of not only healing— but who she is as a person. She shares the complex, beautiful life she lived before the assault, her art and writing, her family life and more, demanding to be seen as a fully-complex person whose story amounts to much more than the hurt brought onto her by another.

“I did not come into existence when he harmed me. She found her voice! I had a voice, he stripped it, left me groping around blind for a bit, but I always had it. I just used it like I never had to use it before. I do not owe him my success, becoming, he did not create me. The only credit Brock can take is for assaulting me, and he could never even admit to that.” - Chanel Miller, Know My Name.

It is easier to paint a broad-stroke over experiences such as these, and time stamp a woman’s success or talents or impact with something outside of her control… thereby demeaning all that has been accomplished by her own merit.

This is where we revert back to the life of Gentileschi and remember that Artemisia’s work can stand by itself, not just within feminist art circles of adoration.

A revolutionary woman of her time, she was unwed through her young years… allowing her the social freedom to mingle— leading her to connect with intellectuals, performers, and various artists, among them Galileo. But the turmoil and trauma of Artemisia’s early life and rape trial, has inevitably overshadowed the less sensational, and less documented, success of all that followed.

When her name is mentioned in art history rooms, many words uttered are that of a wrathful women, revenge art, and highly-emotional compositions. OK— and????

Once, when I had mentioned her in a conversation among peers, an honest, unconscious response from a male artist was, “that’s the baroque painter who was raped right?”

In a series of letters written to one of her patrons, she references her experience as a female painter, “A woman’s name raises doubts until her work is seen”.

Artemisia’s later professional journey was exceptional, leading to the absolutely fair conclusion that the impact and occurrence of her rape was indeed less-significant than what some historians might impose.

Have we heard of or celebrated any of the successes of her past this dark period in her life?

It seems a bit depressing to me that The National Gallery only sought to acquire more of her work after the birth of the #MeToo Movement in 2016, after her work became a symbol of female wrath and revenge… and institutions recognized their own lack of accountability for representing such narratives in these spaces.

Diminishing her work to only be notable for its trauma risks the continual dismissal of female artists being seen as separate, validating the concept that female work is only valuable when autobiographical.

As a female artist, I am tired of feeling the need to identify to the word female more than the word artist. I am exhausted by the need to talk about why my work is important, rather than the work allowing to stand on its own. I am also bored to death by the idea that my work must be thrown into a feminist category in order for its rage to be perceived and justified, as if my own life experiences must be checked and balanced and validated in order to portray its nuance.

“I never knew you could render color so well” murmured a male artist friend at the art exhibition, closely observing the detail on a piece I had completed the month before.

And while it may seem like a compliment in this moment, one where I am vulnerability standing before a piece that depicts the healing process of my own sexual assault— It sounds much more like— “I had no idea you actually held devotion to your craft and maintained such technical skill, because I am too busy classifying you as a woman artist, whose rage takes the forefront and will always be less impactful than mine”

Will we ever be ready for women artist’s to take up space with their precision, their talent, their voice? Or will they forever be viewed through the lens which diminishes their technical power and merit— a disparity forever rooted in the pervasive tendency to categorize our work through the prism of only gendered experiences?

“I am so tired of boring and angry feminist artists on this app” some random man from Iowa comments on my latest TikTok post, one where I discuss the complexities of the motherwound and generational healing and showcase the devotion to my skills and processes.

I don’t want to be defined as an angry, feminist artist.

I want to be an artist.

And as someone who walked away from the experience of her own rape, at the hands of a boy who did more harm than he ever will good…. I stand today as a more empowered, more healed and compassionate version of myself… just as Artemisia Gentileschi did centuries before me— continuing to improve not only her work, but her impact on the world around her, and for all that was possible for those after her—

To remember that though it is woven into the work, and forever our life experience…

I also, with every fiber of my being and knowing in my body— will forever reject and refuse— to be defined by it.